Despite ECB bond purchases

Analysts see the potential for a new euro crisis

May 6, 2022, 2:44 pm

Analysts at Deutsche Bank reject broad assessments of the sustainability of public finances in various EU countries: contrary to popular belief, many countries’ debt has not declined since 2011. In one condition, this may turn out to be a problem.

Dutch bank analysts Maximilian Ulier and Caroline Robb do not rule out a new euro crisis, even as the European Central Bank (ECB) buys government bonds. While the interest costs of all euro countries in relation to economic production have decreased and the average remaining term of their debt has increased, on the other hand, the debt of some countries has increased further since 2011, which will cause the same problems as in 2011. If there is a significant increase in bond yields, analysts write in a comment. “The degrees of independence of the ECB are limited,” she says.

In their study, Uleer and Raab deal with a number of common judgments about the stability of public finances in some euro countries, some of which are incorrect in their opinion. Your statements refer to Spain, France, Italy, Portugal, Ireland, Germany and Greece.

Eurozone countries have reduced their debt since 2011

In her opinion, this is not true and, strictly speaking, it only applies to Ireland and Germany. In most countries, debt grew faster than nominal gross domestic product (GDP). By 2021, Spain’s debt ratio will have increased to 70 percent, France’s 29 percent and Italy 26 percent. Germany, on the other hand, was able to reduce its debt by 13 per cent and Ireland – by 49 per cent – thanks to rapid economic growth.

The average nominal interest rate on government bonds is lower than it was ten years ago

According to the authors, this is true for all countries: in Italy it fell to 2.4 (2011: 4.2) per cent, in Spain to 2.2 (4.3) per cent, in France to 1.6 (3.6) per cent and in Germany to 1.1 (3.3) per cent. .

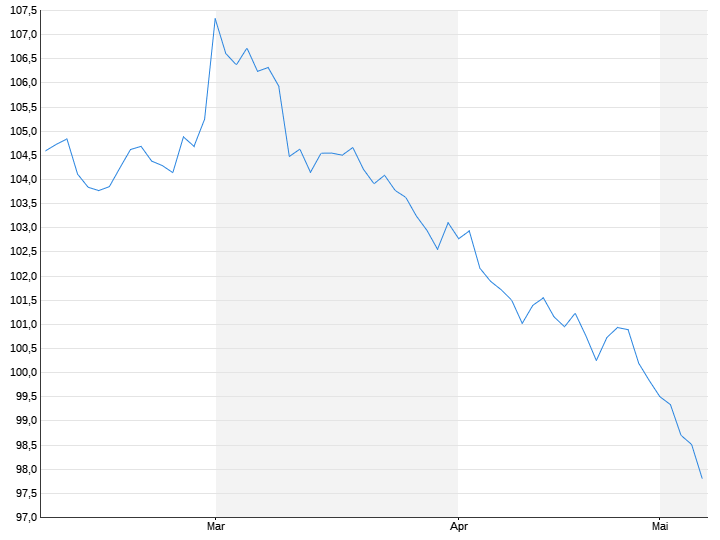

We are far from the return level we saw in 2011

In the opinion of the authors, this is not true. In their view, the most significant measure of this is the ratio of interest expenditure to GDP. Countries with high debt may have lower interest rates but higher interest costs than in 2011. Spain has already come close to this “crucial coupon”. The difference between that and the current interest rate is only 0.3 percentage points, while in Italy it is 0.9 percentage points. It is 1.2 percent in France and Portugal and 2.7 percent in Germany.

The remaining average maturity is much higher than in 2011

That’s right, for example in the case of Greece it was about 28 (9) years and in the case of France it was 8 (7) years. However, the average remaining terms of German (6 years) and Italian (7 years) bonds remained unchanged. The authors also point out that Italy’s maturity profile is focused on the small end. About 35% of government bonds will expire by the end of 2024.

According to Ulier and Robb, the good thing about development over the last ten years is that federal states have been able to reduce their interest costs as a percentage of GDP and extend bond maturities. The bad thing, however, is that debt is on the rise, especially in countries with already high debt. “These countries will have a similar interest expense-to-GDP ratio, with lower yields than in 2011,” she writes.

For example, if yields on 10-year Italian bonds increase by 2 percent next year, analysts predict that by the end of 2025, Italy will have the same interest burden as a percentage of GDP in 2011. “In summary, debt has eased, leaving the ECB with the option of raising rates and ending the buying process,” she writes. But the independence of the ECB is limited. “If interest rates rise sharply for too long, we will face a Euro Crisis 2.0.”

Prone to fits of apathy. Unable to type with boxing gloves on. Internet advocate. Avid travel enthusiast. Entrepreneur. Music expert.