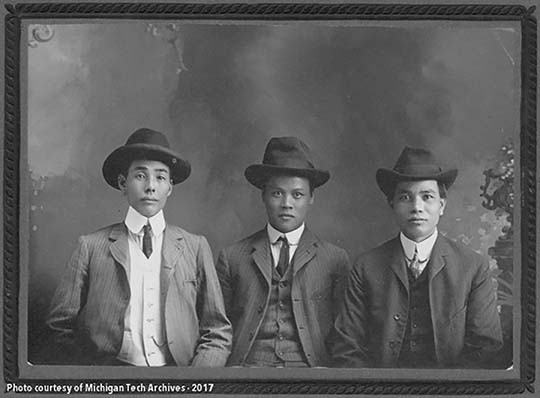

MTU Archives In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, immigrants from Eastern Europe arrived in Lake Superior, but as this undated photo of JW Nara shows, not all immigrants were Europeans, nor did all immigrants want to work in the mines. According to a photo description from the MTU Archive, these three well-dressed Asian gentlemen are “Oriental laundresses”.

When modern technology improved the lives of people in the Copper Country, at least theoretically, something dark was created, and no one – at least openly – spoke out at first. But it was there. Maybe they could not recognize it.

From the second half of the nineteenth century distrust grew between the mining companies and their workers. As the 20th century approached, the area underwent numerous changes in demographics and business.

Initially, the mining companies were small and independent companies. They hired a dozen contract workers and an on-site manager – agent – a clerk, all living in small spaces. In most cases at least one of the directors of the company knew the mining agent and the clerk personally, and the agent knew the men in which he lived and worked. They were small companies.

In the winter of 1846-1847, John H. Forster was the agent of a mine 16 miles from the Eagle River. “A few rough German miners and one or two Frenchmen.” Formed his power and divided it into four “Comfortable cabins in solid pine. Nearly 40 years later, Forster wrote about the practicality of eating with people in small settlements.

However, this gradually changed as many companies were dissolved for various reasons. Other companies are organized, owning one or more of the previous sites, larger than the first pioneering companies. By the end of the nineteenth century, mining companies looked more like modern companies than ever before. Agents who employed hundreds of people did not know their workers personally and probably could not identify someone on a sidewalk.

For example, at Cliff Mine in 1845, Captain Edward Jennings was the first agent there, assisted by one or two clerks and directed by one of the board members. There were two main mine captains in the underground, one for the day shift and one for the night shift. On the surface were the surface captain and his crew.

Just 20 years later, the Kalumet and Hekla mines were not really like that, even in the beginning. After the appointment of Alexander Agassis as agent for the mine in place of Edwin Halbert, the company grew rapidly and employed a large number of workers, and Agassiz did not have time to get acquainted with all the contract workers. Three years after the merger of Calumet and Hekla, they became the largest employer in the region.

“In 1874 we employed 1,616 men”, Agassis said at the annual board meeting in Boston. “In 1899 we employed 4,607 people.”

In contrast, in 1903 the Quincy Mining Company reported an average of 1,624 men that year. Although the C&H force was a quarter of the force, it had a large workforce that not every human being knew.

By comparison, in 1900 he was an agent at C&H, now called the Superintendent or General Manager, an office full of engineers, geologists, draftsmen, clerks, and accountants. There was a chief mining captain, and each pit had captains, team leaders, and department heads.

In later mining companies, the CEO was at a very high level in the food chain, separating from contract workers. The class system in which men lived and worked in the eastern offices was extended to the mining sites.

For example, at Quincy Mining Company “Officers” In the mines – agents, chief mine captains, clerks, etc., lived in houses built by the company much higher than those built for the workers, and the houses of the officers were equipped with steam built by the company’s boilers. With hot and cold running water in their bathrooms, the workers’ homes did not even have a toilet in the plumbing basement. If any worker or his family wanted to take a bath it was taken to a metal tub in the kitchen or paid for from the company’s public bathroom.

In the second half of the 19th century, with the acquisition of long-term migrant workers such as Cornish, Irish, Welsh and German, the ethnic structure of the region began to change. Published February 7, 1914 in the U.S. It received special attention from the Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics Bulletin No. 139, Michigan Copper District Strike.

“Cornish and Scottish were the first foreigners to work in this range [sis]Irish, German, Bulletin on page 144. “They came to the district in the early years of development, and in the first 30 years (1844-1874) produced the largest proportion of miners, most of whom today are Cornisho or their successors.

The report states that it was in the 1870s “Finns, Swedes, Norwegians and Italians began to arrive in the 1980s. Croatians began to arrive in the 1890s, and other Austrians, Hungarians and Poles arrived in the 1990s. The number of finches is twice that of the miners of any other species.

Houghton County had a population of 88,098 in 1910; Kevinau County had a population of 7,156; 8,650 in Ontonagan County. There are 4,459 Englishmen in Houghton County; The Germans represented 1,723; Ireland has only 799 people. In contrast, 11,536 immigrants came from Finland. The number of immigrants from the Austrian Empire was 3,333.

In short, the immigration movement moved east. More and more ethnic groups came to the region from Eastern European countries. They spoke languages they did not know. They dressed jokingly. Her behavior was strange and alien. The mining companies needed them, but they did not need them and did not trust them. In turn, these new Eastern Europeans were aggressive and seemed to think they had an opinion on how the middle- and top management should work and how they should work. This is the beginning of a growing era of animosity between workers and their employees.

Graham Jainig holds a BA in Social Studies / History from the University of Michigan Technological and an MA in English / Creative Nonfiction Writing from Southern New Hampshire University. He is internationally known for his work on Cornish migration to the mining districts of the United States.

Today’s breaking news and more in your inbox

Travel fan. Freelance analyst. Proud problem solver. Infuriatingly humble zombie junkie.