The organization in question is called the Rapid Radio Burst (FRB), a mysterious phenomenon first observed in 2007. FRBs generate a pulse in the radio part of the electromagnetic spectrum; These pulses last only a few thousandths of a second, but produce more energy than the sun in a year.

Some FRBs emit energy only once, but their eruptions are known to be repetitive, including FRB 121102, an object located in a dwarf galaxy 3 billion light-years away. Using a five-meter spherical radio telescope (FAST) in China, a team of scientists decided to conduct a comprehensive study of this repetitive FRB.

Bing Shang, an astronomer at the University of Nevada in Las Vegas, told LiveScience that the campaign was only to collect routine data about this particular institution.

In approximately 60 hours, the researchers observed FRB 121102 eruption 1,652 times, sometimes up to 117 times per hour, much longer than the previously known repeated FRB. The team’s results appeared in the October 13 issue of the journal Nature.

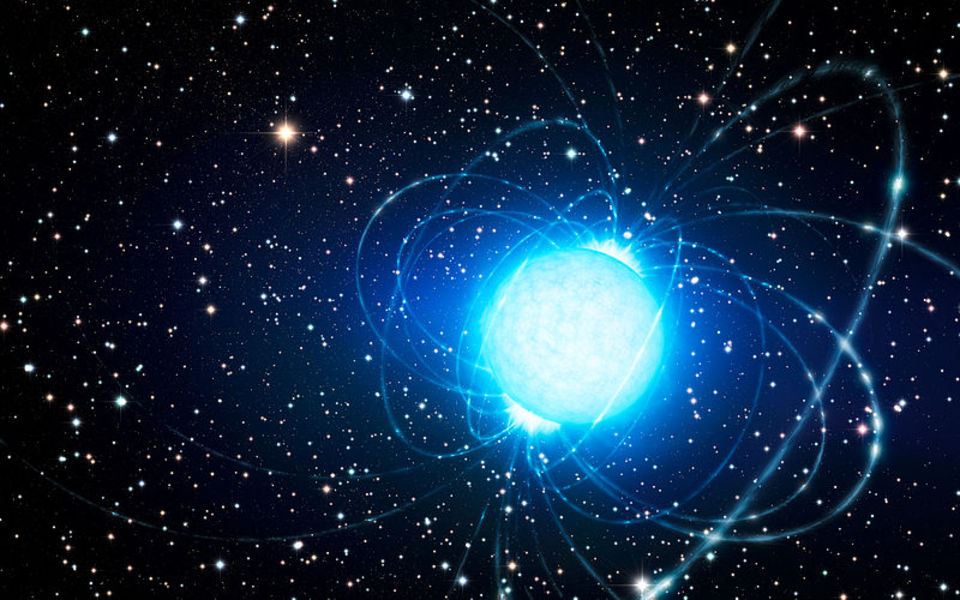

Most FRBs appear in the distant universe, making them difficult to study. But in 2020, astronomers discovered an FRB inside our Milky Way galaxy, allowing them to determine that it was a kind of dead star called a magnet.

A magnet is a type of neutron star with a very strong magnetic field that emits not only high-energy electromagnetic radiation but also X-rays and gamma rays. Magnets produce magnetic fields 1000 times stronger than ordinary neutron stars. It has not yet been determined whether all FRBs are magnetic.

It is also not known how magnets form FRB. But if FRB 121102 is a magnet, the data collected by Shang and colleagues indicate that rapid explosions take place on the surface of the star itself, not in the surrounding gas or dust.

The extreme magnetic fields of magnets – trillions of times stronger than Earth – can sometimes experience violent episodes that emit energy explosions. Astronomers studying the FRB suspect that radio waves can be detected from this initial eruption or from the moment such explosions fall on objects around the star, creating strong shock waves, Zhang said.

Although the data are indicative of a magnetic field interpretation of FRBs, they are known to cause such energy explosions, so the findings are not yet conclusive, said Victoria Caspie, an astronomer at McGill University in Montreal, told LiveScience.

The magnet found in our galaxy last year did not emit so many explosions in such a short time. But it’s because she’s older, maybe the younger magnets can match FRB 121102’s observations, they added.

“Now the question is for theorists,” young magnets need to determine if this is enough to explode repeatedly, Caspi said.

Prone to fits of apathy. Unable to type with boxing gloves on. Internet advocate. Avid travel enthusiast. Entrepreneur. Music expert.