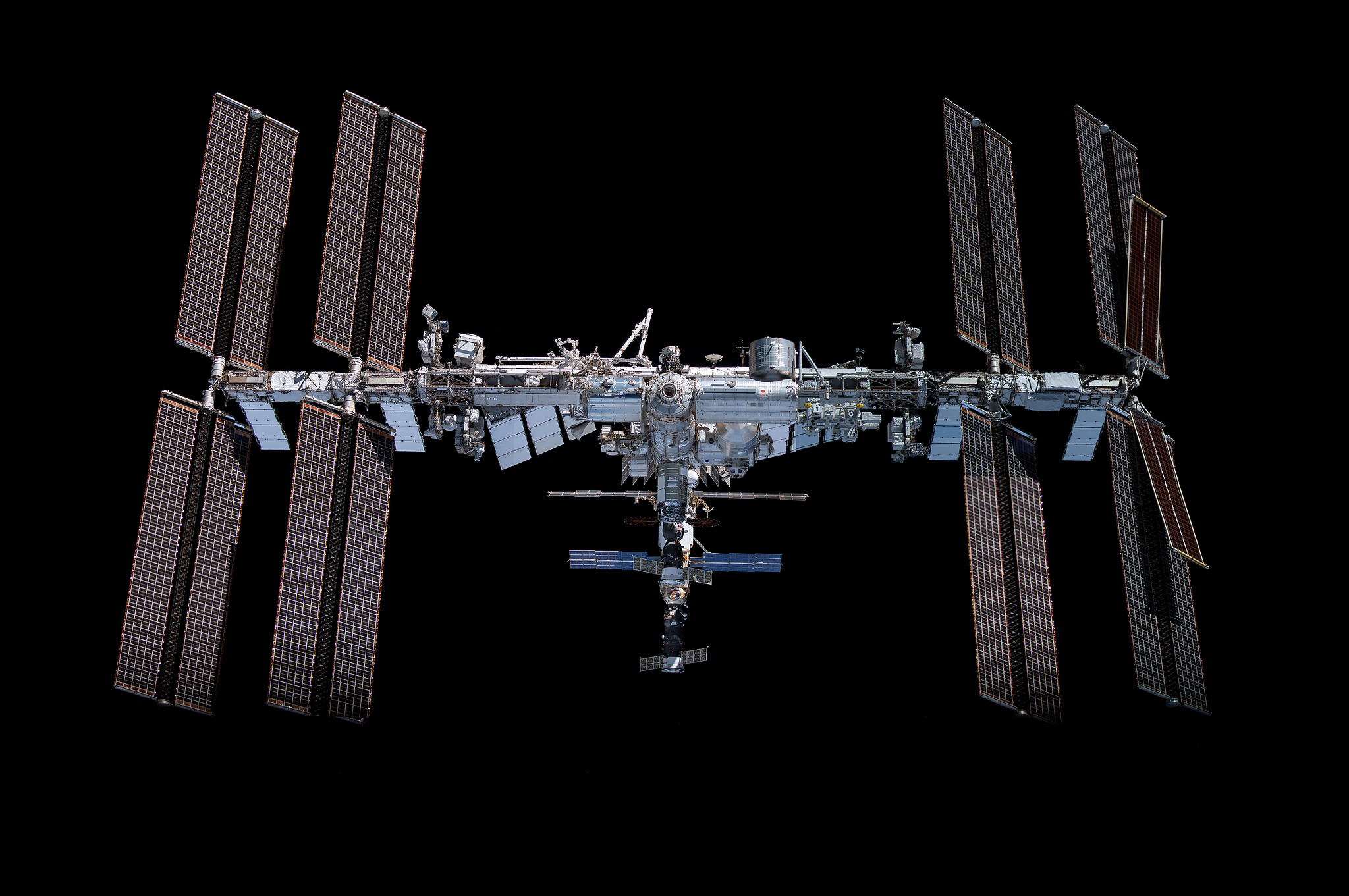

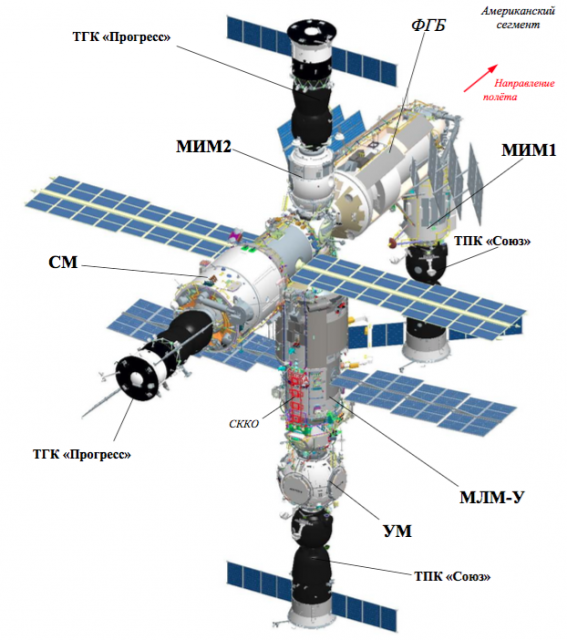

The International Space Station (ISS) has become the center of controversy over the occupation of Ukraine. Dmitry Rogozin, head of the Roscosmos, made more or less threatening statements announcing his intention to separate the Russian segment from the ISS in order to “drop” the station. Is it possible? As we have seen in one Previous postIn fact, the ISS relies heavily on the Russian section — especially the Zvezdá module and Progress spacecraft — to gradually elevate its orbit and implement certain orientation change strategies. The US segment (USOS) – including ESA (Columbus), Japan (Kibo) modules and the Canadian Canaderm 2 robotic force – does not have its own propulsion system. However, while it is not physically possible to separate the Russian segment from the ISS, it can be a logistic nightmare, as multiple external cables are required to cut and disconnect multiple external cables, including electrical, so do not forget to rely on the Russian segment. USOS in terms of power supply.

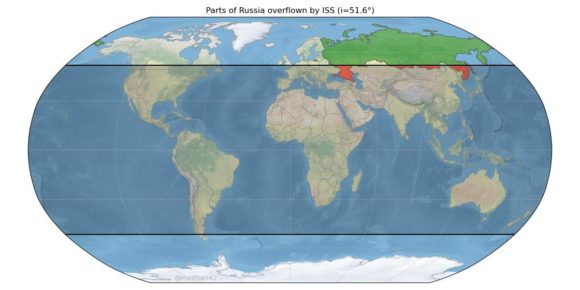

In any case, it is practical that Russia can distinguish the latest modules (boat, prechal, for example), although the advantage of this measure is that it creates a station of its own, although it stays only for a short time, which, at the very least, is highly questionable. Do not forget that Roscosmos’ great and ambitious plans are going through the construction of a new station. ROSS, Completely Russian, in polar orbit. But what if Russia decides to shoot itself in the leg and abandons the ISS or “refuses” to raise the station’s orbit? If so, it all depends on the action of solar energy (which further expands the upper layers of the atmosphere and causes more friction). In the absence of Russian segment engines, the ISS will remain in orbit for one or two years before uncontrolled re-entry (although the station may have to be abandoned earlier for safety reasons). Its orbital inclination is 51.6º, which means that it can fall anywhere on the planet between 51.6º north and 51.6º south, i.e. the most densely populated areas on Earth. Studies indicate that up to 16% of the station can survive reentry. At about 420 tons in mass, it is the largest human object ever collected in space, so the risk of material or personal damage is small but not insignificant.

According to the calculations of Jonathan McDowell, The ISS spends 70% of its orbit overseas, 4.1% on China, 3% on Australia, 2.8% on Russia, 1.4% on Crimea, Kazakhstan, Canada and Brazil and 1.2% on the US. China, Australia and Russia are most likely to be affected if the ISS leaves. Interestingly, if Russia “leaves” the ISS tomorrow, the station will re-enter unrestricted access in 2024, even as the current cooperation agreement between the project partners expires. Until a few months ago, everyone expected that all participants would approve the extension of useful life until 2028 or 2030, but, after the occupation of Ukraine, now nothing is certain. It should be noted that so far there are only temporary plans for organizing a restricted re-entry. In fact, even the software for reentry operations is not ready. The problem with re-entering the ISS is that it is so large that a very strong propulsion system must be used to ensure that atmospheric disintegration occurs above the “Spacecraft craft” in the South Pacific. Also known as SPOUA (The South Pacific Ocean is an uninhabited area), Near the famous Pacific Pole of Accessibility, better known Nemo Point.

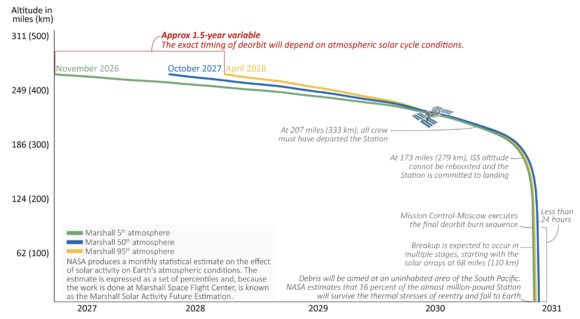

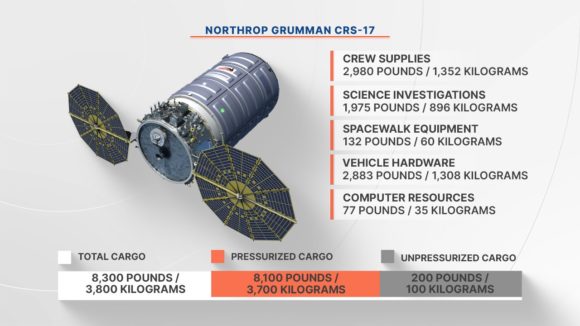

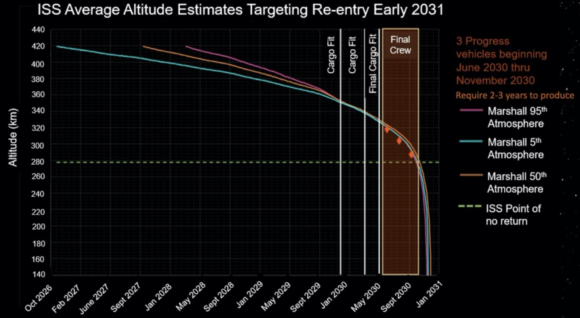

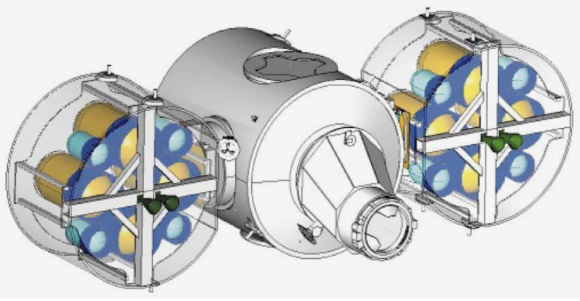

However, as we have already mentioned, only the engines of the Progress ships and the Zvezdá module are available, and they are not particularly powerful. The main engine of the Progress has a thrust of 300 kg, while that of the Suzuki is 315 kg, but the main drawback is that the Progress engines only allow ignition lasting up to 900 seconds. It) limits cooling with the fuel layer). For years, the option of using a specific module, such as the European ATV, or some modified cargo vehicle, was considered for this task, but the current plans are to use three Progress ships in addition to the Svezdai, it is clear. , Can be implemented only with the cooperation of Russia. In the controlled reentry strategy, the disintegration date is set first, and then, depending on solar activity, the station’s orbit begins to lower two or four years ago. In NASA’s latest situation, which is expected to have a controlled restart in December 2030, the station’s orbit will gradually decrease from 2026 or 2028. By mid-2030, the ISS will reach an altitude of about 330 km. The staff left. Three Progress spacecraft are scheduled to launch between June and November 2030 to implement breaking strategies. By the end of the year, the orbit will have dropped to about 270 km, the “non-return height”. Below this height – logically, depending on solar activity – it is considered impossible to maintain the orbit of the ISS with Zvezdá engines. Zwesda’s final ignition will ensure that the station is destroyed above the Pacific.

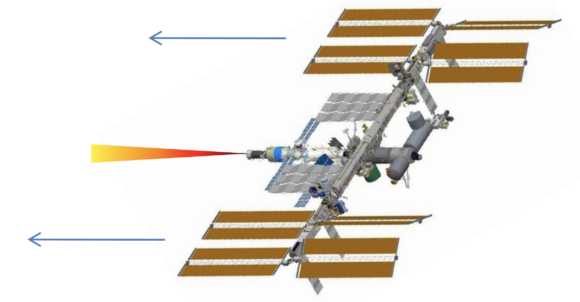

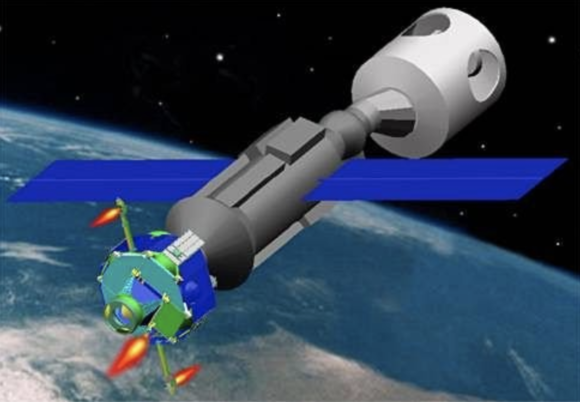

But if Russia decides not to cooperate — that would be seriously irresponsible — what options do the remaining ISS partners have? First, the development of new Cygnus cargo ships capable of changing the station’s orbit must be completed (and, in addition, the Cygnus Atlas V or Vulcan must be launched, as the Antarus rocket was built in Ukraine and equipped with Russian engines, which are not available). These ships — perhaps Boeing’s Starliner and SpaceX’s Dragon (the second with cargo capacity in its trunk) – will help keep the ISS in orbit until it decides what to do. It may take time to build a specific module, such as ICM (Interim control module) Since 1990, it has been designed to replace Zvezdá until its launch (eventually it will not be needed). Or a completely different module (perhaps a modified Axiom module or another private company).

The difficulty in this situation is that the new spacecraft will have to be ready within a year to prevent the ISS from re-entering uncontrollably in the event that Russia leaves the station. Will it take time to keep ISS in orbit? In any case, the fact that the head of Roscosmos is trying to unleash such threats, even as Russia continues to cooperate with the ISS, reveals just how bad the atmosphere of space cooperation between Russia and the United States is. The Western partners of the ISS must be prepared for the worst.

Prone to fits of apathy. Unable to type with boxing gloves on. Internet advocate. Avid travel enthusiast. Entrepreneur. Music expert.