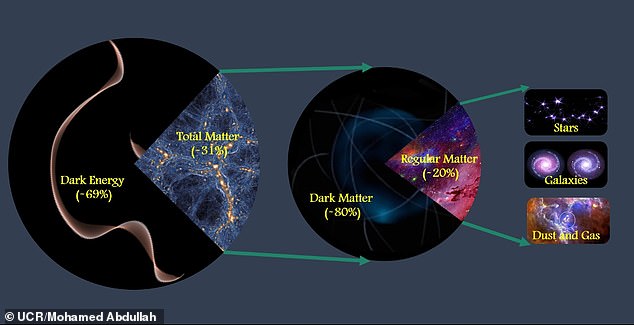

Two-thirds of the known universe is made up of ‘dark energy’ and only 31 percent of matter – experts find that most of it is made up of ‘dark matter’.

Cosmologists from the University of California at Riverside have used a number of tools and new ‘galactic orbit’ technology to determine how much matter is in the universe.

To calculate this, they first explained the subject by looking at how neighboring galaxies orbit in one galaxy, and then measured the entire universe.

The team found that 31 percent of the universe is matter, and the rest is dark energy – an ‘unknown energy energy’ that scientists do not yet understand.

Of the 31 percent, the majority – 80 percent – is dark matter, which we have only discovered through gravitational interaction with other objects.

‘The researchers claim that this is one of the most accurate measurements ever made using the Galaxy Cluster technique.

Scientists at the University of California, Riverside, have found that 69 percent of the universe’s dark energy, 31 percent matter, and 80 percent dark matter.

On a universal scale, the amount of known matter is very small, according to the study authors – gas, dust, stars, galaxies and planets are only 20 percent.

If all the objects in the universe were spread out evenly in space – it would have ‘the density of six hydrogen atoms per cubic meter’.

“However, since we know that 80 percent of matter is actually dark matter, the vast majority of the subject matter is not hydrogen atoms, but a kind of matter that cosmologists do not yet understand,” said the lead author, Muhammad Abdullah.

Determining exactly how much matter is in the universe is not an easy task, as it depends on observations and simulations, cosmologists explained.

As part of their measurement, the team compared their results with other predictions and computer simulations to find that the ‘Goldilocks’ calculation was ‘correct’.

To calculate the contents of a cluster, the team calculated the number of galaxies based on the orbit of others, and then measured it for the entire cluster.

Combining these calculations with galaxy clusters and comparing them to simulations of matter expected in the universe gave the team the most accurate figures ever recorded.

“We succeeded in building one of the most accurate measurements ever made using the Galaxy Cluster technique,” said co-director Gillian Wilson.

This is the first use of a galaxy’s orbit – to determine the amount of matter in a single galaxy by looking at how other galaxies orbit.

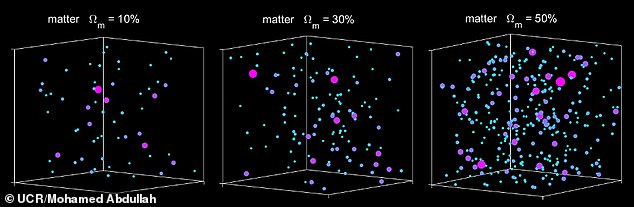

“A higher percentage of matter will result in more clusters,” Abdullah said.

This image from Hubble shows a galaxy cluster – researchers used data from a collection of similar galaxies to estimate the total mass of the known universe.

Like Goldilocks, the team compared the number of galaxy clusters they measured to predictions from numerical simulations, which determined the answer to be ‘correct’.

The “Goldilocks” challenge for our team is to measure the number of clusters and then determine which answer is “correct,” Abdullah said.

‘But the mass of any galaxy cluster is difficult to measure accurately because most things are dark, so we can’t see it with a telescope.’

Dark matter is a relatively unknown substance that is thought to be the gravitational ‘glue’ that binds galaxies together.

Calculations show that many galaxies would rupture instead of spin if they were not captured by large amounts of dark matter.

Unfortunately, this has never been observed directly, and can only be seen by gravity with other types of matter.

To overcome this difficulty, astronomers have developed a cosmic instrument called ‘galwite’, which measures the mass of a galaxy cluster using the orbits of its member galaxies.

Researchers have used their device in observations made by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) to create a generally available catalog of galaxy clusters, the ‘GalWQat 19’.

Finally, they compared the number of clusters in their new catalog with simulations to determine the total mass of the universe.

“One of the great benefits of using our Galveight Galaxy orbit technology is that our team has been able to determine the mass of each cluster individually, rather than relying on more indirect and statistical data,” said Anatoly Klipin, the third co-director.

By combining their quantities with those from other teams that used different techniques, they were able to determine the best integrated value.

The findings were published by Journal of Astronomy.

Prone to fits of apathy. Unable to type with boxing gloves on. Internet advocate. Avid travel enthusiast. Entrepreneur. Music expert.